- Climate

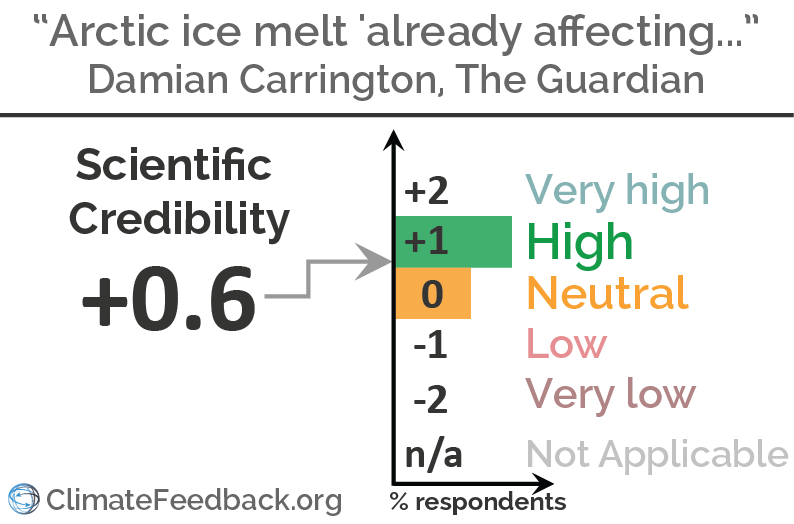

Analysis of "Arctic ice melt 'already affecting weather patterns where you live right now'"

Reviewed content

Published in The Guardian, by Damian Carrington, on 2016-12-19.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This article in The Guardian discusses the influence of Arctic warming on mid-latitude weather patterns. The Arctic is warming faster than the global average, and the possibility that this warming is driving a change in the behavior of the jet stream—and the mid-latitude weather that results—has seen lots of coverage in the past few years.

While the article includes interviews with a number of scientists doing research on these patterns, the scientists who reviewed it explained that the conclusions expressed aren’t completely representative of current scientific knowledge: There remains real uncertainty about the link between Arctic warming and certain mid-latitude weather patterns, which the article does not make entirely clear to the reader.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Associate Professor, University of Exeter

The article nicely introduces some of the emerging science linking Arctic climate change to extreme weather at lower latitudes. There are no major inaccuracies and the author has sought expert comment from several prominent scientists. However, the article fails to fully capture the large uncertainty about how Arctic warming may influence weather in places further south and how big this effect might be. For example, the article draws heavily on a scientific hypothesis that Arctic warming causes a more meandering jet stream and slower moving weather systems (e.g. blocking). This is a credible hypothesis supported by a few peer-reviewed publications (most prominently by one of the scientists interviewed), but there are other papers that have failed to identify such a link, or argued against one.

In short, there is no scientific consensus on whether or not Arctic warming causes larger jet stream wiggles or more persistent weather. The jury is still out. Whilst some of the scientist’s quotes do hint at unknowns and ongoing scientific debate, the overall tone of the article gives the impression the science on this topic is more settled than it actually is.

Senior Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

I think the writer basically captured the essence of the scientific information provided to him, although some simplifications make the state of the knowledge sound more sweeping than the consensus view in the community. There are skeptical voices in the community whose views differ from those presented in this article. A more complete story could have included them to provide an alternative perspective on the role of a changing Arctic.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

The author has sought out and quoted relevant experts in the field, and presents specific factual information that is largely accurate regarding a topic that is of considerable interest to both researchers and the public at large. My primary concern with this piece is that it overstates scientific confidence in the linkages between Arctic sea ice loss and mid-latitude weather (especially regarding connections to specific events, like Hurricane Sandy) and fails to make clear that this area remains a topic of very active research. It also uses some language that trends toward hyperbolic, especially in discussing “superstorms”.

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Michigan

The article spans a wide range of related, but complex topics. Had it focused on just one, such as the potential link between Arctic sea ice melt and midlatitude atmospheric blocking patterns, the writer could have perhaps provided a more thorough summary of what researchers know and, just as importantly, how confident they are in their results.

While this article provides insight on how Arctic warming and melting sea ice may affect midlatitude weather, it misleadingly presents the sea ice-albedo feedback as the only contributor to Arctic temperature amplification.

Lecturer, University of Oxford

The article seems to faithfully summarise the views of these scientists. However, this is a relatively small group of researchers, and many in the field would give a more cautious story given current uncertainties.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“The chain of events that links the melting Arctic with weather to the south begins with rising global temperatures causing more sea ice to melt. Unlike on the Antarctic continent, melting ice here exposes dark ocean beneath, which absorbs more sunlight than ice and warms further. This feedback loop is why the Arctic is heating up much faster than the rest of the planet.”

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Michigan

This statement correctly identifies how the sea ice-albedo feedback contributes to Arctic temperature amplification, but incorrectly implies that it is the only process responsible for the enhanced warming. While some studies have concluded that the sea ice-albedo feedback is the primary driver of Arctic amplification [1-2], other feedbacks [3-4], internal atmospheric variability, and decadal variations in sea surface temperature and ocean circulation [5], may have contributed as much, if not more, to the Arctic tropospheric temperature increase.

1. Screen and Simmonds (2010) The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification, Nature

2. Taylor et al. (2014) A Decomposition of Feedback Contributions to Polar Warming Amplification, Journal of Climate

3. Pithan and Mauritsen (2014) Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models, Nature Geoscience

4. Winton (2006) Amplified Arctic climate change: What does surface albedo feedback have to do with it?, Geophysical Research Letters

5. Perlwitz et al. (2015) Arctic Tropospheric Warming: Causes and Linkages to Lower Latitudes, Journal of Climate

“The jet stream forms a boundary between the cold north and the warmer south, but the lower temperature difference means the winds are now weaker. This means the jet stream meanders more, with big loops bringing warm air to the frozen north and cold air into warmer southern climes.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

The statement regarding what the jet stream is (a “boundary between cold north and warmer south”) is essentially correct, and there is indeed evidence that the north-south temperature difference has decreased in some regions.[1] But there remains considerable scientific uncertainty regarding whether the jet stream is actually “meandering more” in a general sense, and whether these large jet stream meanders are actually caused by sea ice loss.[2-3]

1. Francis and Skific (2015) Evidence for a wavier jet stream in response to rapid Arctic warming, Environmental Research Letters

2. Barnes and Screen (2015) The impact of Arctic warming on the midlatitude jet‐stream: Can it? Has it? Will it?, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change

3. Screen and Simmonds (2013) Exploring links between Arctic amplification and mid-latitude weather, Geophysical Research Letters

Senior Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The first sentence is grounded in solid meteorology, since the strength of westerly winds aloft is basically proportional to the north-south temperature difference. The second sentence is also supported by evidence, although not quite as solidly. The sinuosity of the upper-level westerlies generally does vary inversely with the wind speed, but there are exceptions. When the jet stream meanders a lot, then warm air is brought northward and cold air spills southward.

“Furthermore, researchers say, the changes mean the loops can remain stuck over regions for weeks, rather than being blown westwards as in the past. This “blocking” effect means extreme events can unfold.”

Senior Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

First, I think the word should be “eastwards”, not “westwards”. Second, although the loops do sometimes remain stuck for weeks, the sentence makes it seem as if this is the new normal. Instead, a weaker jet stream ought to increase the persistence on various time scales, but more often being days instead of weeks. The second sentence is partly true, in that atmospheric blocking patterns often do cause extreme weather events, but extreme events can also occur under other conditions, including very strong jet stream winds (e.g. atmospheric rivers).

“Severe ‘snowmageddon’ winters are now strongly linked to soaring polar temperatures, say researchers, with deadly summer heatwaves and torrential floods also probably linked.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

Arctic temperatures have certainly been much higher than the long-term average in recent years, and the extreme warm anomalies this autumn and early winter have been particularly noteworthy. Further, there is a growing body of evidence linking Arctic sea ice loss and/or polar-amplified atmospheric warming to changes in mid-latitude atmospheric circulation*. However, this subject represents a very active area of research and there remains genuine scientific uncertainty regarding specific linkages between ongoing Arctic sea ice loss and specific kinds of extreme weather (like the heatwaves, floods, and snowstorms mentioned here). Moreover, the effects under consideration would likely have different regional manifestations. Therefore, the above statement overstates scientific confidence in such linkages and is overly broad in a geographic sense.

- Francis and Vavrus (2012) Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes, Geophysical Research Letters

- Cohen et al. (2014) Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather, Nature Geoscience

- Overland et al. (2016) Nonlinear response of mid-latitude weather to the changing Arctic, Nature Climate Change

Lecturer, University of Oxford

“Strongly linked” is an overstatement here. There is some evidence, but I don’t think a majority of climate scientists would make claims as strong as these.

“It’s safe to say [the hot Arctic] is going to have a big impact, but it’s hard to say exactly how big right now.”

Lecturer, University of Oxford

This statement is unclear. Arctic warming will clearly have a strong impact on the midlatitudes in the future (certainly by the end of the century). Whether it has had a noticeable effect so far is a lot less clear.

“In those years, the jet stream deviated deeply southwards over those regions, pulling down savagely cold air. Prof Adam Scaife, a climate modelling expert at the UK’s Met Office, said the evidence for a link to shrinking Arctic ice was now good: ‘The consensus points towards that being a real effect.’”

Senior Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The first sentence is correctly describing how the jet stream tends to move equatorward during the negative phase of the North Atlantic (or Arctic) Oscillation [NAO and AO, respectively], which was very prevalent in those years. Negative phases of the NAO or AO strongly promote more extreme cold in middle latitudes during winter. As for a “consensus”, that depends a lot on who you ask. This topic of potential Arctic-middle latitude connections is a controversial one, so there isn’t a lot of consensus on the overall role of the Arctic at this point. I think the closest we have to a consensus is the persuasive evidence that sea ice loss in the Barents-Kara Seas during autumn-winter promotes extreme cold downstream over eastern Asia via a stronger Siberian High Pressure Cell.

Lecturer, University of Oxford

This refers to a southward shifted jet in response to sea ice loss (a negative North Atlantic Oscillation pattern). It’s not clear at all that this is the same kind of behaviour as suggested by the quoted scientists.

“The connection between the vanishing Arctic ice and extreme summer weather in the northern hemisphere is probable, according to scientists, but not yet as certain as the winter link.”

Lecturer, University of Oxford

The winter link is not certain either. As above, there is some evidence for a North Atlantic Oscillation response but still several conflicting studies.

Senior Scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Again, it depends who one talks to about whether “probable” is the correct term. There have been numerous articles making this claim and providing plausible evidence for it, but a well-accepted physical explanation has yet to be established, in my opinion. The dynamical mechanisms linking sea ice anomalies to mid-latitude weather during winter are easier to understand than those during summer. Different but more complex linkages might well exist during summer to explain some of the observational evidence correlating sea ice anomalies with extreme summer weather.

“Another consequence of the fast melting Arctic raises the possibility that there may be even worse extreme weather to come, according to a few scientists: titanic Atlantic superstorms and hurricanes barreling across Europe.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

This statement does not accurately describe an outcome that is widely supported in the scientific literature. It is certainly true that Arctic sea ice is decreasing at a rapid rate, and that further sea ice loss is highly likely in the future. It is also plausible, and supported by existing research, that present and future sea ice loss may alter the atmospheric circulation in ways that affect the likelihood of certain kinds of weather events*. But the claim regarding “Atlantic superstorms” and “hurricanes barreling across Europe” seems fairly hyperbolic.

- Overland et al. (2016) Nonlinear response of mid-latitude weather to the changing Arctic, Nature Climate Change

- Kug et al. (2015) Two distinct influences of Arctic warming on cold winters over North America and East Asia, Nature Geoscience

- Zhang et al. (2016) Persistent shift of the Arctic polar vortex towards the Eurasian continent in recent decades, Nature Climate Change

“This means a region of the north Atlantic is becoming relatively cool and this exaggerates the contrast with tropical waters to the south, which is the driver for storms. In the worst case scenario, said the renowned climate scientist Prof James Hansen, this ‘will drive superstorms, stronger than any in modern times – all hell will break loose in the north Atlantic and neighbouring lands’.”

Lecturer, University of Oxford

I agree that the superstorm suggestion is very speculative. In one paper we looked at a similar scenario and saw a clear increase in the number of storms, but not their intensity, though that was just in one climate model.

- Brayshaw and Woollings (2009) Tropical and Extratropical Responses of the North Atlantic Atmospheric Circulation to a Sustained Weakening of the MOC, Journal of Climate

“I would certainly not call such [superstorm] scenarios ridiculous,” said Coumou. “But it is speculative – we don’t have the hard evidence.”

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

The superstorm scenario rests on a number of assumptions, especially that the rate of ice melt from Greenland (and Antarctica) will accelerate very rapidly. Definitely still in the realm of speculation.