- Climate

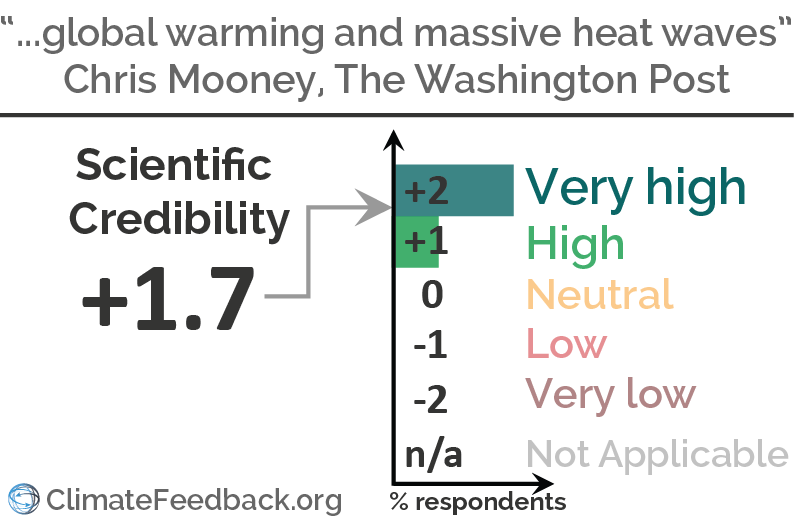

Analysis of "What science can tell us about the links between global warming and massive heat waves"

Reviewed content

Published in The Washington Post, by Chris Mooney, on 2016-07-21.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

The Washington Post reports on the “massive heat wave” that is currently affecting the US and explores the question of how such events are related to human-induced global warming.

The scientists who have reviewed the article confirm that it accurately describes the state of scientific knowledge on the topic. While the observed increased frequency, severity and duration of heat waves in some parts of the world are among the most certain impacts of climate change, calculating any increases to the current heat wave’s probability or intensity as a result of global warming will require a specific study (called an “event attribution study”), which has not yet been performed for the current event as of July 25th.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Research fellow, University of Melbourne

This is a well-written article that provides a good overall discussion around the connection between climate change and the ongoing US heat wave. In the absence of a specific event attribution study the role of climate change in this event can’t be quantified, but Chris Mooney provides an insightful overview of the role of climate change in heat events generally.

Deputy Director Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford

I do not find anything wrong with the article. And it makes the key point that robust event attribution is now possible. However, the article could better help readers understand what ‘event attribution’ is in contrast to ‘predictions’. The article makes the point that it is now possible to attribute individual classes of extreme events to climate change: eg heat waves in a specific region and season. It is not clear in pointing out that the reason for having to do a specific ‘attribution study’ is to quantify the role anthropogenic climate change played in an event given the observed class of heat wave.

While on average we see an increase in heat wave frequency and intensity, there are parts of the world where there is actually hardly any increase (e.g. parts of India in the pre monsoon season) while for others the likelihood of certain types of heat waves to occur has increased at least 10 fold (eg Central Europe).

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Senior researcher, KNMI (The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute)

The article gives a fair and balanced view on the topic.

The one proviso that is not made that could have been added is that increasing air pollution with aerosols that block sunlight can counteract the effect of greenhouse gases on heat waves, as was the case in Europe up to the mid-1980s and is the case now in some other parts of the world such as India. However, the opposite is happening in the United States where clearer skies also increase the risk of severe heat waves. There are other factors, such as drying soils, that can exacerbate a heat wave, so indeed a specific study is needed to know how much the present heat wave can be attributed to global warming.

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

This article is very good because it relies on quality documents including a National Academies report and the US Climate Assessment.

It quotes several scientists who reflect the broad consensus of scientists who work on extreme event attribution.

The story makes the point that with global warming, extreme heat waves will become more common and more intense, yet just as you cannot say with 100% confidence that a smoker would not have died of cancer had he not smoked, we cannot with 100% confidence attribute any particular heat wave to climate change. However, just as statistics, combined with mechanistic understanding, clearly demonstrate that smoking cigarettes causes cancer, statistics, combined with a mechanistic understanding of climate physics, clearly demonstrate that the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is causing an increase in the frequency and intensity of heat waves.

Overall, an excellent article.

Research Scientist, University of Colorado, Boulder

This well-explained article accurately represents the current science for understanding the contribution of climate change to extreme events such as heat waves.

Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany

A fair summary of the scientific current understanding of the observed increases in heat waves and their relations with global warming.

Senior researcher, UK Met Office

A balanced overview.

Research Scientist, Climate Change Research Centre, The University of New South Wales

This article is very accurate, a little oversimplified in some areas, but that can be difficult to overcome.

Specialist in climate scenarios, Ouranos

The journalist is right regarding his main point: it cannot be told that global warming is the cause of a specific extreme event (unless it could not have existed without global warming); the issue must be addressed with probabilities, comparing all events we experience with all events we would have got without global warming.

However, the point is not well illustrated by the current heat wave in Eastern US, since this region is precisely known for showing negative long-term trends in many extreme heat indicators.

In summary, the main point is insightful and applies globally, but the journalist does not illustrate it with the most appropriate event, because projected increases in the indicators of extreme heat over Eastern US have not clearly got out of the natural variability so far.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from Chris Mooney; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“And the gist is that when it comes to extreme heat waves in general — heat waves that appear out of the norm in some way, for instance in their intensity, frequency, or duration — while scientists never say individual events are “caused” by climate change, they are getting less and less circumspect about making some connection.”

Research fellow, University of Melbourne

This is certainly true. Over the last few years we’ve seen more and more attribution statements related to heat waves (where there is higher confidence in the climate change link compared with other extremes, such as heavy rain events) and scientists have become more confident in making this connection.

Senior scientist, The Norwegian Meteorological institute

“Climate change” is by definition a shift in the weather statistics, such as the curve that describes the likelihood of temperatures exceeding a certain threshold [see figure below]. The temperature has a statistical character that is close to being bell-shaped (normal distribution), which implies that high temperatures are expected to be more frequent with a global warming – unless the typical range of temperatures (standard deviation) or shape of the curve changes as well. Climate is the typical character outlined by this curve (probability density function) describing the probabilities, whereas weather is each different data point on which this curve is based. When referring to one event – one data point – one talks about weather. Weather is not the same as climate, but they are related: climate is the expected weather.

Figure illustrating how a change in climate influences the frequency of extreme heat events: an increase in the average temperature (upper panel) causes a large increase in the probability of extreme hot events; a change in the climate variability (lower panels) can further alter the frequency of extreme events. – adapted from IPCC report (2001)

“The U.S. National Climate Assessment found that U.S. heat waves have already “become more frequent and intense,” that the U.S. is shattering high temperature records far more frequently than it is shattering low temperature records (just as you’d expect), and that it is seeing correspondingly fewer cold spells.”

Research fellow, University of Melbourne

This is true and is also consistent with findings from other areas of the world. For example, Dr Sophie Lewis led work that showed in Australia there have been 12 times as many hot records compared to cold records since 2000.

“Typically, in such an attribution study, scientists will use sets of climate models — one set including the factors that drive human global warming and the other including purely “natural” factors — and see if an event like the one in question is more likely to occur in the first set of models. Researchers are getting better and better at performing these kinds of studies fast, in near real time.”

Research fellow, University of Melbourne

This is an accurate description of how extreme event attribution studies are conducted.

“this event poses severe risks to health — particularly for children and the elderly […] an extreme 2003 heat wave that affected Paris and Europe, and which has indeed been connected to climate change through statistical attribution analysis […] killed hundreds of people in Paris and London, and a recent study attributed at least some of those deaths, themselves, to climate change.”

Scientist, University of Bonn, Germany

Only mentioning the deaths in two cities understates the danger of heat waves. The number of people who died in the 2003 heat wave is estimated to be in the tens of thousands. This article estimates it was 70 thousand additional deaths.

Professor, University of Washington

The majority of injuries, illnesses, and deaths during heatwaves are preventable. A robust literature base documents individuals at higher risk during heatwaves, such as adults over the age of 65 years, infants, individuals with certain chronic diseases, and others. Heatwave early warning and response systems save lives; expanding these systems to more cities and increasing awareness of the health risks of high ambient temperatures could increase resilience as heatwaves increase in frequency, intensity, and duration.

Another issue is that growing confidence that climate change is increasing the probability of heatwaves means some deaths during heatwaves could be attributed to climate change.

Research Scientist, Climate Change Research Centre, The University of New South Wales

When the 2003 European heatwave occurred it killed 70 000 people. At the time the likelihood of that event occurring had doubled due to human influence. Now an event like this is 10 times more likely due to human influence.

References:

- Stott et al (2004) Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature.

- Christidis et al (2015) Dramatically increasing chance of extremely hot summers since the 2003 European heatwave. Nature Climate Change.

- Trigo et al (2005) How exceptional was the early August 2003 heatwave in France?. Geophysical Research Letters.