- Climate

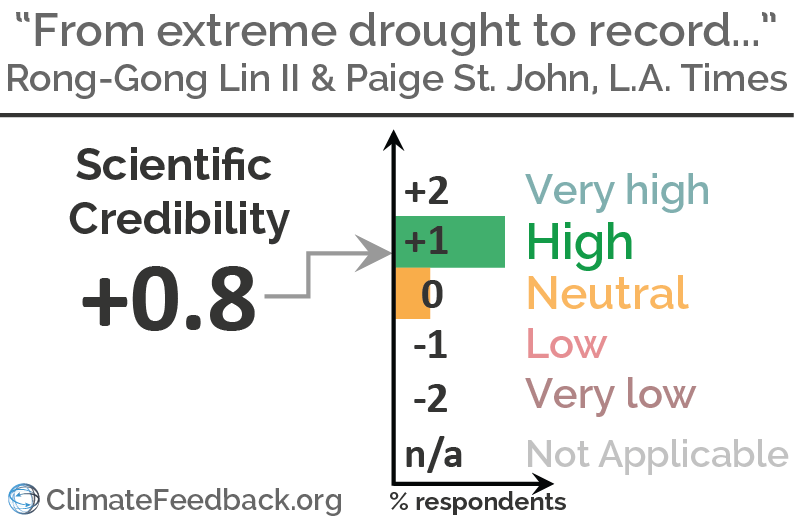

Analysis of "From extreme drought to record rain: Why California's drought-to-deluge cycle is getting worse"

Reviewed content

Published in Los Angeles Times, by Paige St. John, Rong-Gong Lin II, on 2017-04-12.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This article in The Los Angeles Times discusses the recent exceptionally wet winter in California, which followed several years of extreme drought conditions. These events are put into the context of trends in recent decades and the future projections of continued human-caused climate change. Warming temperatures are expected to increase the magnitude of both dry years (since evaporation increases with temperature) and wet years (since a warmer atmosphere has a greater “water-holding capacity”), which can sound counterintuitive at first.

Scientists who reviewed the article found it to be a generally accurate description of the state of scientific knowledge on these complex topics.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

This timely article accurately characterizes the broader climate context of California’s rapid transition from drought to flood.

Project Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

The article is accurate and highlights the challenges that California’s water resource managers are facing due to climate change. There are some issues with differentiating natural climate variability and forced climate change but the main points are correct.

Associate Editor, Nature Climate Change

This article is balanced and accessibly written, and its description of the recent history of California’s weather is accurate and clear. The authors do not substantiate all of their claims, nor do they explain mechanisms underlying the changes they discuss, but for its intended purpose—an article contextualizing recent California extremes within the historical record and how they might be changing—it seems to fit the bill.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“The extreme cycles of dry and wet weather appear to have been intensifying over the last three decades.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

There is indeed observational evidence that California precipitation extremes—and the atmospheric phenomena that cause them—have occurred more frequently in recent years*, although that signal has only recently emerged from the “noise” of natural climate variability. There is also an expectation that such swings between extreme dry and extreme wet will continue to become more pronounced as the climate warms*.

- Swain et al (2016) Trends in atmospheric patterns conducive to seasonal precipitation and temperature extremes in California, Science Advances

- Diffenbaugh et al (2015) Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California, PNAS

- Wang et al (2015) The North American winter ‘dipole’ and extremes activity: a CMIP5 assessment, Atmospheric Science Letters

- Yoon et al (2015) Increasing water cycle extremes in California and in relation to ENSO cycle under global warming, Nature Communications

- Berg and Hall (2015) Increased Interannual Precipitation Extremes over California under Climate Change, Journal of Climate

- Gao et al (2017) Twenty-First-Century Changes in U.S. Regional Heavy Precipitation Frequency Based on Resolved Atmospheric Patterns, Journal of Climate

A. Park Williams, Assistant Research Professor, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory:

Yes, variability in California precipitation appears to have been higher in the past 3-4 decades than the previous decades, but it is not (and cannot be) clear that that the variability in precipitation is actually currently in the act of increasing. I say that it cannot be clear because it takes decades of data (say 2-3) to characterize the current “variability” of the climate. Based on my calculations, variability in annual precipitation totals increased considerably during the second half of the 1900s and then has remained at this relatively high level for the past couple decades, but has not clearly continued to increase. This latest swing from record dry to very wet in the last year is consistent with high variability, but it’s a single event and not necessarily indicative of a trend.

There are some logical links, however, that support the inference that wild swings like the current one should be expected to become more likely. First, droughts are becoming increasingly impacted by warming temperatures. Even if precipitation behavior didn’t change at all, years with low precipitation would correspond to less and less water availability for humans and ecosystems. Second, current climate models project variability of California precipitation to increase in the future, with an increase in the frequency of years with very high precipitation totals becoming detectable sometime in the first half of this century, and an increase in the frequency of years with very low precipitation totals becoming detectable in the second half of this century*.

It should always be remembered, however, that models have a tough time with California precipitation. California is right on the boundary between projections of drying to the south and wetting to the north. I personally believe the basic expectation that California precipitation should become more variable, but beyond that I don’t yet put much stock in what models have to say about the future of precipitation in California.

So, variability has increased overall in the last century, and this is consistent with what models project to occur as a result of greenhouse-gas driven climate change. The increase in variability hasn’t been a monotonic trend, however, and it is not obvious from the data that the trend is continuing now as rapidly as it was in previous decades. This suggests that other low-frequency processes are also at play that influence decade-to-decade changes in the variability and magnitude of annual precipitation totals, making it particularly difficult to determine the degree to which this current event can be attributed to climate change. Nonetheless, California would be wise to prepare for more events like these.

- Berg and Hall (2015) Increased Interannual Precipitation Extremes over California under Climate Change, Journal of Climate

“Warm weather worsened the most recent five-year drought, which included the driest four-year period on record in terms of statewide precipitation. California’s first-, second- and third-hottest years on record, in terms of statewide average temperatures, were 2014, 2015 and 2016.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

This claim is supported by a wide range of scientific research*. Record warmth during the recent drought has also been directly implicated in some of the most iconic drought impacts, such as extreme lack of Sierra Nevada snowpack* and a large increase in wildfire intensity*.

- Diffenbaugh et al (2015) Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California, PNAS

- Williams et al (2015) Contribution of anthropogenic warming to California drought during 2012–2014, Geophysical Research Letters

- Belmecheri et al (2016) Multi-century evaluation of Sierra Nevada snowpack, Nature Climate Change

- Yoon et al (2015) Increasing water cycle extremes in California and in relation to ENSO cycle under global warming, Nature Communications

Associate Editor, Nature Climate Change

There is evidence that warmer temperatures across the globe affect large-scale atmospheric dynamics, which in turn feed into regional weather patterns. The relevant example here is the argument that a warming Arctic will reduce large-scale temperature gradients in the atmosphere, which will in turn affect (and be affected by) the complex path that storms follow across the Pacific Ocean as they approach the North American west coast.

While the extent to which this has already happened is debatable*, there is agreement that it will be a robust signal if Arctic warming continues unabated*.

- Cohen et al (2014) Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather, Nature Geoscience

- Overland et al (2015) Nonlinear response of mid-latitude weather to the changing Arctic, Nature Climate Change

- Screen (2017) Climate science: Far-flung effects of Arctic warming, Nature Geoscience

“And this winter’s near disaster at the overflowing Lake Oroville was in part caused by warm storms too.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

The skewed rain-snow ratio this season certainly contributed to some of the precipitation-related impacts this winter. While winter 2016-2017 was not exceptionally warm in the Sierra Nevada, especially relative to recent record-warm years, it was still warmer than average. In middle elevation zones of the Sierra Nevada, precipitation fell as rain rather than snow more often that would have historically been the case—leading to a snowpack that significantly lagged overall liquid precipitation (although both were well above average). (See this article in Eos.)

“Not everyone is convinced that the evidence is in that climate change is responsible for extreme swings between drought and deluge.”

Climate Scientist, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Los Angeles

There is a considerable and growing body of scientific evidence (see above references) demonstrating that California will likely experience increasingly large swings between extreme wet and extreme dry conditions. The evidence that climate change has already caused such an increase is somewhat less strong—mainly because there are relatively few extreme events in the historical record from which to draw such conclusions.

Therefore, this statement is imprecise, and may be misleading if it is intended to convey that scientists substantially disagree regarding the likely future increase in California precipitation extremes. Whether such an increase is yet detectable in the historical record is indeed uncertain; there is much greater certainty regarding the likely direction of future change.

“‘The dry periods are drier and the wet periods are wetter,’ said Jeffrey Mount, a water expert and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.”

Project Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

This is seen in assessments of atmospheric reanalyses, which show a decreasing frequency of rain-producing weather systems over California but higher rain rates over the last 35 years*.

- Prein et al (2016) Running dry: The U.S. Southwest’s drift into a drier climate state, Geophysical Research Letters